Morning is the best time to write because the world isn’t up yet. I’m not just talking about a.m. in general, but about 2:30 and 3 and 3:30 and 4 and 4:30 and 5, and even 5:30. Things get shot when the postal workers come to work beneath my office at 6, for then I hear the rumblings of practical work. This, along with the rising sun, ruins everything for me.

Morning is the best time to write because the world isn’t up yet. I’m not just talking about a.m. in general, but about 2:30 and 3 and 3:30 and 4 and 4:30 and 5, and even 5:30. Things get shot when the postal workers come to work beneath my office at 6, for then I hear the rumblings of practical work. This, along with the rising sun, ruins everything for me.I woke up at 2:30 this morning—again. You cannot believe how tired I am by 5 p.m.

It is only good for a man to be alone when he is writing. How can writers collaborate? In the world of words there is room for only one mind. Charge it with a little caffeine and see what happens. Turn on an electric fan so that the white noise of the fan merges with the white noise of the brain, and see what happens. I cannot imagine being unable to track down a thought stream at 3 a.m. with a cup of coffee and a fan running. At noon, it’s another story.

It is only good for a man to be alone when he is writing. How can writers collaborate? In the world of words there is room for only one mind. Charge it with a little caffeine and see what happens. Turn on an electric fan so that the white noise of the fan merges with the white noise of the brain, and see what happens. I cannot imagine being unable to track down a thought stream at 3 a.m. with a cup of coffee and a fan running. At noon, it’s another story.Writer’s block is simply performance anxiety. It is worrying how you sound and how you will be received; whether you’re good; whether your wife will like it; how many people you will offend; whether or not you’ll sound smart; can you compete with Henry Miller?

Some people live their whole lives chained to performance anxiety. You know them by the hospitals they are in; they get ulcers and die early. They never do anything original. They only do what they think other people want them to do. And if they think they can’t do something better than everybody else, they don’t do anything. (This is too common. People forget that they are unique. It is important to learn to embrace unique imperfection. The alternative is a long and miserable life. The world’s great people boldly publish their self-perceived failings.)

There are two modes in which one writes, and these are 1) creation mode, and 2) editing mode. (I think many of these lessons will work for life. As we go, apply these things to your living.) A writer is both creator and editor. The editor must sit on the bench while the writer writes—and vice-versa—and this is the secret to breaking through writer’s block (and to living life).

A writer in creation mode cannot afford to fret over how the words come out, just that they come. Sitting for minutes staring at a wall in search of the perfect word is fatal to the Muse. There will be plenty of time later for second-guessing. In creation mode, forget the perfect word. The important thing is to come close.

Turn off the dictionary and thesaurus and turn on the mind. Loose the mind from its cage. (If you can do this after the sun comes up, more power to you.) The mind will rub its eyes and look around, hardly believing it’s free. (How often do you let your mind out? We take our dogs for walks, but not our minds. We let our dogs pee on anything and we relish the tail wagging, but not so with our minds.) A free mind is a happy mind. It is a tail-wagging mind. So many filters in life stop up the mind. The key to writing honest prose (and to living an honest life) is to dispense with as many filters as possible. I understand that we must employ filters to function in society and avoid jail time, but the secret of the filters is to leave them off until editing mode. In creation mode, go with the stream of thought without filters. Jump into the stream with whatever words you know and paddle like hell after the thoughts. It helps to know how to type.

Winston Churchill painted. One day, he couldn’t start a painting. He stared at his canvas, unsure how to begin. Just then, a friend drove up, a woman, who was also a painter. She asked what the trouble was, and he told her. She said, “May I?” and he said, “By all means.” She grabbed a brush, sloshed it in some blue, and just like that started streaking the canvas with it to make sky. She hardly gave it thought. (Well, the woman pre-dated the Nike Company. Her motto was: “Just do it.”) Churchill said it was the last time a blank canvas ever intimidated him.

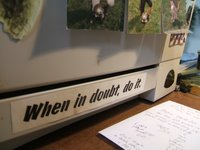

This is why I have a little piece of paper taped to my printer that says, “When in doubt, do it.”

This is why I have a little piece of paper taped to my printer that says, “When in doubt, do it.”Oh, and have something to say. Otherwise, you’re screwed.

© 2006 by Martin Zender