Without my wife, I would fade. I would still do what I do, but it would be a fading do. I miss her. For all our differences, her presence somehow preserves me. It makes me a better man than I would be without it. I have wondered if I would sacrifice my kidney for Melody. My first reaction is that I would want two kidneys. There are lots of poisons in my body that I need rid of. I value ureters and all tubes leading to my bladder. Scan the scum off my blood, is what I say to my body in prayers at night. But how could I not give a kidney to preserve my beloved? How could I not sacrifice an organ for the organ that is my completion? Nothing is the matter with Melody’s kidneys. I speak out of fear. No one gets dialysis here. My selfishness only goes so far. I would give Melody my heart. I am tired of living anyway. I am tired of all the things I do in Melody’s absence. I am tired of the way my heart quivers like a frog when Melody is not here. Yet I would request anesthetic. Yet they would never bring me out, and neither would I would them to.

Melody could then do a half-marathon maybe five minutes faster.

I would never give her my thoughts; I love her too much.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Sunday, April 30, 2006

Friday, April 28, 2006

MELODY GOES TO NASHVILLE ALONE

Melody left for Nashville this morning. I took a sunny picture of her and kissed her good-bye. I set her up with a CD player adapter for the car, and all the old ZenderTalks from 2004. She has her shoes and her money and a cell phone and books about happy women and a new feminine hair ribbon that she tied back parts of her hair with. Melody looks good in the sun and in the moon.

Melody left for Nashville this morning. I took a sunny picture of her and kissed her good-bye. I set her up with a CD player adapter for the car, and all the old ZenderTalks from 2004. She has her shoes and her money and a cell phone and books about happy women and a new feminine hair ribbon that she tied back parts of her hair with. Melody looks good in the sun and in the moon.I waved to her as she drove away. I had made her coffee, and she took that with her. I wrote her a card that she won’t see until she unloads a book from the car in Nashville. Larry and Jamie will look after her.

Melody likes to drive by herself. A car is a private place for a person to think in. A person in a car can easily imagine that he or she controls his or her own destiny; look at all the controls that are in the car. Cars are relative paradises of relative control, what with all the knobs, the switches and the tiny levers. Airline pilots must feel like gods. It is control we lack, so it is control we look for, even if it is only a treble adjustment or a flap switch. Turn down the treble and retract the flaps; see what little it takes for a Deity-like feeling. But see, as well, how hard it is to manufacture it: plastic factories (or plastic factories) come, lots of heat comes, labor unions come.

I loved my wife through the window as I waved at her. I hope she comes back. I don’t want her to die. I drove past the cemetery on the way back to work and I thought, What if Melody dies? What if she gets in a car crash and dies? What if that was the last picture I ever took of her? What if, thirty years from now, I am still looking at that picture and kissing it and telling it that I love it?

The tears came, but I pushed them back. I don’t understand why I pushed them back, because I almost always let them come. I am not one to push back tears. Maybe it is because I think that Melody will have a good time. I am glad the car is sunny and that I made Melody a good cup of Folgers and poured it thoughtfully into her green, plastic mug. She will listen to ZenderTalks and music and will be happy. She will be proud of me for making the ZenderTalks. She likes that I love God. It is the most important thing to her, to have a husband and children who love and honor God. Women need men to be something in this world.

If a man hopes to attract a woman in this world, he cannot hang out on a street corner and watch them. He must do something to make a difference in the world. A woman will notice when a man lives from his gut. (It helps if the man keeps his shoes clean.) A woman always notices a man with a purpose. Women do not care for the male ass as men care for the ass of the female. Women appreciate a man with good solid rump, but women will go first for the man of purpose. If the man of purpose has a splendid ass, then so much bonus. It is all bonus. It is a bonus for which women ought to thank the Deity.

I was walking through the grocery store dressed spiffily one day when the cashier girl said, “You look like a man with a purpose.” I was so flattered. I’ve never forgotten that. It had the same effect on me as the effect on a woman would have should a man say to her: “You are so beautiful.”

I discovered Melody in 1982 through her eyes and, later—when she first came down the steps of her home—through her ass. These led to deeper chambers. I love most of the chambers. I know who Melody is now, and she knows me. This is comforting on a level that I have not named. On another level, it is disconcerting; the name of this level is “disconcerting.” Other people have named it “baggage.” The baggage level works in concert with other, more pleasing platforms. Levels and platforms: this is the mix that every married couple celebrates and endures. God has arranged it thus to build character and to warm a fire in the fireplace.

I hope my wife does not die.

Melody has told me, “If something ever happens to me, I want you to remarry. I want you to find another goddess.”

Why would I want to talk or think about that? I guess for the same reason that crazy people pre-buy grave plots. Melody is trying to leave me something in the terrible wake of her absence. Something like a legacy or a will. But I cannot think about that on top of what I think of as I drive past the cemetery this morning, ten minutes after waving good-bye to my beloved partner of twenty-four years. Tomorrow morning, my partner will walk and run 13 miles as fast as she can with her friend Jamie during what meteorologists are calling to be a thunderstorm. The drama should end in less than three hours. The thunderstorms of tomorrow will contrast with the sunshine of today to make a pattern of the eon for we who appreciate fireplaces.

I’ll probably die first anyway.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Friday, April 21, 2006

THE MARTIN ZENDER DRILLING COMPANY

In case you do not know it, today is National Drilling Day in Bosnia. This is a Bosnian holiday only. Only in Bosnia do people celebrate this day. People in Bosnia will be drilling today, you can bet that. And not only dentists, mineworkers and army sergeants, but everyone. Everyone will be drilling something, even if it is only a 52-foot well.

If this day is not marked on your calendar, then you must return your calendar to its place of purchase for a full refund, demanding that no questions be asked. Tell the vendor: “I am returning this calendar because it has failed to alert me to National Drilling Day. You see? I am now pointing to the twenty-first of April, and it is nothing but an empty white square with nothing written in it except the number ‘21.’ Does this seem right to you? Does it seem thorough enough for me? Does it seem politically correct to anyone? Shah! Do not even think of asking a question! A globally aware person such as myself must be kept abreast of the ways of other peoples and their ceaseless miseries, and not merely of the phases of the moon or when Canadians celebrate Thanksgiving.”

National Drilling Day did not become a recognized holiday until 1986, which is why I did not know about it as a third-grader at Saint Bernadette School of the Burned Martyrs in 1968. For it was then that I began The Martin Zender Drilling Company.

The Martin Zender Drilling Company consisted of me, a pencil, and a desk. I remember the day I began The Great Hole. I gently sat the sharpened point of a number two lead pencil against the surface of my wooden desk. I held it there between my two palms like a Saturn V rocket poised for the moon between two giant palms. But instead of launching it, I began rolling my “rocket” back and forth between my palms in the manner of an upright lathe. That’s how it all began.

The Martin Zender Drilling Company consisted of me, a pencil, and a desk. I remember the day I began The Great Hole. I gently sat the sharpened point of a number two lead pencil against the surface of my wooden desk. I held it there between my two palms like a Saturn V rocket poised for the moon between two giant palms. But instead of launching it, I began rolling my “rocket” back and forth between my palms in the manner of an upright lathe. That’s how it all began.I told my friend Brian Malinowski, who was seated next to me, “See here, Brian. See here what I’m doing. See what a genesis is here. I am beginning a hole, Brian, but not just any hole. No, but this is to be The Great Hole. Are you comprehending it? From the looks of you, I must wonder. Shake yourself from the stupor of unbelief! Comprehend the era! For in less than two months, I shall have drilled through this entire desk. And yet this is the beginning of it—right now. You are here to see it, to witness the inauguration of it. This is bigger than Lincoln’s speech at Valley Forge.”

I paused to look around me. Mrs. Ditchwald busied her silly self writing ridiculous-looking numbers on the blackboard. All the other students were either minding the numbers or dreaming of bologna sandwiches. The clock clicked another minute into my promising future while a strange gaseous residue hissed from the coils of a green-silver nozzle on the bottom coils of the heater thing by the window. I lowered my voice. “It is not an auspicious beginning, Brian, I grant you that. But it will be auspicious when you see the results two months from now.”

Each day I patiently drilled The Great Hole. I drilled and I drilled. Brian Malinowski told other students about it, and they all came by at different times to witness my progress. Some whistled in awe. Others asked to see my pencil. “You mean my drill?” I would say. Most classmates had at least some hazy notion of my genius. Others openly acknowledged it. More importantly, each and sundry admired my spunk and pluck. One girl even said to me, “Martin, I admire your spunk and pluck.”

Each day I patiently drilled The Great Hole. I drilled and I drilled. Brian Malinowski told other students about it, and they all came by at different times to witness my progress. Some whistled in awe. Others asked to see my pencil. “You mean my drill?” I would say. Most classmates had at least some hazy notion of my genius. Others openly acknowledged it. More importantly, each and sundry admired my spunk and pluck. One girl even said to me, “Martin, I admire your spunk and pluck.”Fortunately for me, it was at this precise juncture that I required a secretary.

“Kelly McGowan,” I said. “You are an extremely intelligent girl. And you wear pastel-colored skirts several inches above your knees. Better legs, I have never seen.”

“And you are Martin Zender,” she said. “Driller of Holes and Failer of Math.”

“Driller of The Great Hole,” I corrected. We both looked down at my speedily-rotating drill, and at the considerable sawdust accumulating faster than Kelly’s puckered, red lips could blow it away. “It’s coming along,” I said. “But things are getting complicated now.” I tried to sound grim and optimistic simultaneously. “This is week three. I’m still five weeks away from blasting through this puppy. But I’m finding it hard to drill and at the same time mentally write my next screenplay. Do you understand what I’m telling you?”

“No.”

“It’s a strain on me, Kelly, to push The Juggernaut of Creativity, along with this pencil. It’s all metaphoric, I fear. I fear I may be going mad. It’s getting to be too much for one man. I’m only human here.”

“What are you saying, Martin?”

“I’m saying that—Would you like to be secretary of The Zender Drilling Company?”

Kelly blushed from the tip of her auburn hair to the frill on her little white socklets. It was so gratifying to see. “I am looking for part-time work,” she said. She looked down and blushed even more. “I do appreciate what you’re doing, Martin. I believe in you.” Without warning, her head snapped up. “Do I have to take dictation?”

Kelly blushed from the tip of her auburn hair to the frill on her little white socklets. It was so gratifying to see. “I am looking for part-time work,” she said. She looked down and blushed even more. “I do appreciate what you’re doing, Martin. I believe in you.” Without warning, her head snapped up. “Do I have to take dictation?”I put down my drill and lit a cigarette. “No. I only need you to file reports. I may need you for publicity. You’ll have regular hours and full benefits, I promise.”

“Paid maternity leave?”

“Of course. I’m covered for that.”

She looked down again. “It’s just that things happen.”

“Kelly. I know. Forget it. I already told you: paid maternity leave.”

“What about holidays?”

I put the top of a crooked index finger beneath her pretty chin and brought her head up to look at me. “Never, Kelly. Do you hear me? I promise. Not one holiday, not even St. Francis of Assisi Adopt a Sick Bird Day.”

Kelly let a smile escape her luscious lips. “Okay, Martin. I’ll do it. I want to do it. I think about you all the time. I believe in you. I believe in what you’re doing. I’ve always been fatally attracted to boys like you.” I had a good command of the bottom of her chin, so Kelly looked over at The Great Hole with her eyes only. “I think you can finish this in four weeks, if you put your mind to it. But listen. You have got to promise me that you won’t let a word of this slip to Mrs. Ditchwald.”

I let go of Kelly’s chin, rolled my own eyes, and flicked a long ash from my cigarette seventeen feet into a golden watering can, where it hissy-fitted out. “C’mon, Kelly. The success of this whole project depends on Ditchwald’s ignorance. But why would she even care about The Great Hole? Look at her.”

We both looked at Mrs. Ditchwald. She wore the long cotton dress of a math person, and flat shoes.

We both looked at Mrs. Ditchwald. She wore the long cotton dress of a math person, and flat shoes.“She’s a pawn of the system,” I said. “And look at those ridiculously flat shoes; she could heat up the bottoms of those things and iron shirts with them. She’s an institutional schlep. All she cares about is her crazy math problems and not appearing sexy. Do you think she has a boyfriend? Do you think Janitor Fife ever gives her the look-see?”

“She’s married, for God's sake.”

“Such petty minds as hers I will never understand. Will you? Do you care how many apples Bill has left if his father gives him sixteen but then takes away three?”

“Actually, Martin, yes, I do. It is imperative that I know. I’m trying to get straight A’s in this class.”

I thought of rolling my eyes again, but decided at the last minute to control them. I could not afford to offend Kelly. I took another long drag from my cigarette and looked up at the brown underbelly of a light fixture, where I blew a large cumulonimbus of smoke. “What could a person such as Mrs. Ditchwald have to do with something as stupendous as The Great Hole?”

Kelly looked up to see what I was looking at. I suppose she thought it was a spider. Actually, there was a spider now, a small brown one, descending on a strand of web; I mentally named it Vaughn Spindlenuts. “Oh, I don’t know,” said Kelly. “Maybe she’d be mad about it because it’s her math class and you’re dissing it.”

Oh, how Kelly McGowan could work the italics function! I flicked another ash, harder this time, sixty-nine feet out the open window and into a thirty-gallon vat of holy water, where it hissed, vaporized and died. I looked down to pet my hole. I slowly stroked it. “Kelly. Your tone has changed. You know it has. Do you know how much that hurts me?”

Oh, how Kelly McGowan could work the italics function! I flicked another ash, harder this time, sixty-nine feet out the open window and into a thirty-gallon vat of holy water, where it hissed, vaporized and died. I looked down to pet my hole. I slowly stroked it. “Kelly. Your tone has changed. You know it has. Do you know how much that hurts me?”“Martin, please…”

I needed a fat lie just then, and it came to me. “Ms. McGowan. I don’t need you, you know. I can do this by myself. I’m offering you a job, and a good one. If you don’t see this as history, then think of it as regular employment. Think of it as another entry on your resumé, if that’s what it takes for you. This is a job, and I need a secretary. Case closed.”

I had hurt her feelings. I instantly regretted my words, instantly wished I could take them back. I would get on my knees and beg Kelly if I had to.

Just then, something snored. As I located the source, inspiration struck. I gestured to our right, where Brian Malinowski made the obscene noises of an unconscious dork. A string of drool hung from his bottom lip, seeped over the round edge of his desk, and reached to the floor where it formed a lake that reflected his fat face. “Look at Brian there,” I said. “Do you think he knows how many apples Bill has left?”

Just then, something snored. As I located the source, inspiration struck. I gestured to our right, where Brian Malinowski made the obscene noises of an unconscious dork. A string of drool hung from his bottom lip, seeped over the round edge of his desk, and reached to the floor where it formed a lake that reflected his fat face. “Look at Brian there,” I said. “Do you think he knows how many apples Bill has left?”“No way,” said Kelly, returning to her old self. “In fact, he told me yesterday that he thought Bill had bananas. Can you believe that?” Kelly shook her head and sighed. “He’s a fricking moron.”

I dropped my cigarette to the floor and fatally injured it with the toe of my loafer.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” I said. “And I think he might be addicted to pornography. He was with me at the beginning, but now look at him. He couldn’t stay the course. He forsook me, just like the disciples forsook Jesus. In fact, look around you, Kelly. They have all forsaken me. No one understands—not one! Only you know what I’m about.” I stared hard at Kelly’s awesome blue eyelids. “You alone are left.”

Kelly came aboard that minute, and did things ever change in my drilling speed. In four weeks, the hole was finished, just as Kelly said it would be. To this day I do not believe that I could have finished The Great Hole a week ahead of schedule were it not for the support of a woman, for the belief of a woman, for the inspiration of a woman.

Brian missed us passing through the last centimeter of desk, as did every other moron in my class. Only Kelly was there. She cried, as did I. It was a moment to remember. We held the pencil together and drilled, Kelly and I, palms pressing palms as that final eight-sixteenths of a centimeter disappeared beneath the lead of our pencil/drill.

Mrs. Ditchwald pulled me harshly from the room the next afternoon, pulled me by the tender apex of my right ear into the hall, and down to the office of Sister Dominna. It is possible that a boy jealous of my relationship with Kelly tipped off Ditchwald—but who cares how she found the hole? Sometimes a person cannot feel pain. And sometimes, if the high is high enough, a person can even smile through it.

“So many students sit in that desk throughout the day!” spat Dominna, cracking her pointy black knuckles. “And yet Ditchwald tags you.” She narrowed her eyes. “I have insight into you and that little hole of yours, Zender. May I salvo a query into the hows of your arrest?”

“I think that you already know, Herr Dominna. So say it. Say it with all your might for the benefit of all my readers through the eons of time. Say it with gusto before the commencement of my sacred punishment.”

“I think that you already know, Herr Dominna. So say it. Say it with all your might for the benefit of all my readers through the eons of time. Say it with gusto before the commencement of my sacred punishment.”“Gladly, Master Martin: You signed the damn thing!”

Sometimes, if the high is high enough, a person can smile through any sort of temporal discomfort.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

SLEEPING APART

It has traveled through the grapevine that some near and dear ones want Mr. Zender to go to Nashville with his wife.

Some people believe that married couples should sleep together every night of their lives. I was once among this contingent. This belief is due to the supposed moral necessity of couples feeling miserable apart—even if the respective parties wouldn’t. This false moral necessity is a smokescreen for a fear of oneself and of one’s own thoughts. It is fear that one may not be happy in one’s own skin or, worse, be temporarily relieved by the absence of one’s lover.

Contrast this with the true moral necessity of fearless happiness. It is my present opinion that those incapable of solo contentment are incomplete humans. And two incomplete humans do not a single person make. Instead, they make snide remarks about one another. Or one is made impatient while the other grits the teeth; or one makes cuts while the other bears the wound. The two become one, yes, but sometimes only one check mark on the right side of a marital statistic. Each wishes the other to become what they can never be; what fun. (Don’t try it at home, kids.) Many couples keep sacrificing until nothing remains but Emerson’s hobgoblin: foolish consistency. So thank God for that ever-reliable distraction:

Grandchildren.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Some people believe that married couples should sleep together every night of their lives. I was once among this contingent. This belief is due to the supposed moral necessity of couples feeling miserable apart—even if the respective parties wouldn’t. This false moral necessity is a smokescreen for a fear of oneself and of one’s own thoughts. It is fear that one may not be happy in one’s own skin or, worse, be temporarily relieved by the absence of one’s lover.

Contrast this with the true moral necessity of fearless happiness. It is my present opinion that those incapable of solo contentment are incomplete humans. And two incomplete humans do not a single person make. Instead, they make snide remarks about one another. Or one is made impatient while the other grits the teeth; or one makes cuts while the other bears the wound. The two become one, yes, but sometimes only one check mark on the right side of a marital statistic. Each wishes the other to become what they can never be; what fun. (Don’t try it at home, kids.) Many couples keep sacrificing until nothing remains but Emerson’s hobgoblin: foolish consistency. So thank God for that ever-reliable distraction:

Grandchildren.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Friday, April 14, 2006

PRETEND YOU’RE UNCLOVEN

I don’t know if this has anything to do with the arrival of my new hammock and the netted wombness of my new personality, but Melody and I have decided that she should go to Nashville for the half marathon with Jamie and her boyfriend Larry (on the 29th of this month) by herself and leave me at home. Maybe it was my suggestion. I am getting the feeling that Melody needs time by herself. We all need that. I am very sensitive to a woman’s moods and feelings, especially when that woman vents through her God-given vents. Do not think badly of Melody. I yell and cry as well, but usually in the sanctity of my office. When I try to put my fist through my door at various times and for various reasons, it is a sanctified time. I must have quiet and the angels in attendance. I must have a somber and holy place in which to heave pocket change. It is within the confines of my priestly vestibule only that I throw potatoes against walls and clean my desk with my forearm. Remind me to tell you sometime, in detail, about how I clean my desk during times of great stress. It is a most rapid and most efficient method—involving the forearm—and I am thinking about utilizing it at all other times, due to its rapidity and efficientness.

I would not want to be a woman in this life unless I could do it while preserving my male understanding of sex. But neither would I necessarily want to line up with 23,000 other people in Nashville to be segregated into “bins” and walk 13.1 miles over a carpet of paper cups. I love my wife and I need her, just as Jamie needs Larry and Larry needs Jamie. Larry says that Jamie is “so beautiful,” and she is. Jamie is beautiful. But Melody is beautiful, too. The first thing that attracted me to Melody was her eyes, but that was only because the first picture I saw of her framed her neck and head. Had she been framed from the neck down, my eyes would surely have gravitated toward her ass.

My wife has a beautiful ass. It is better than Jamie’s, I think. Does that offend Larry? Does it offend Jamie? Does it offend my readers? Does it offend the Maker of the Female Ass?

My wife has a beautiful ass. It is better than Jamie’s, I think. Does that offend Larry? Does it offend Jamie? Does it offend my readers? Does it offend the Maker of the Female Ass?

(It will offend Melody, I'm sure. She did not approve the use of this photograph, and did not pose for the sake of this blog. I talked her into this shot a year and a half ago for inclusion in my marriage book, Shagah. I was studying the waist/hip ratios of women and the effect specific ratios have upon males. Hey. Somebody had to do it. Melody eventually nixed the photo for inclusion in the book, and so did my agent at the time, who was a woman; she was probably jealous. But I'll be darned if this photograph is going to collect dust in a box in the closet.)

No doubt Larry will say that Jamie’s ass is better than Melody’s. That’s fine. Of course he would say that. He must say it. Is it true? I don’t know. I admit that I have not analyzed Jamie’s ass. To do so would be improper. I have a feeling that it's probably terrific. I do not wish to call in an objective party. If I did, I would call my friend Jim. But he thinks that his wife has the best ass, so there you go. To each their own asses.

Or, if you wish, you can choose not to discuss it. Or to appreciate it. Or to write about it. You can go ahead and call your own ass a “hindquarters.” Or “a butt.” Call it "a tush," if you want. You can call it an Oreo, for all I care. You can call birds “women.” You can call women “birds.” You can call chipmunks “birds,” if that’s what hangs your hammock. You can eat lots of food and make your ass grow to the size of a zeppelin, if that’s what you want to do. You can refuse to exercise your God-given ass and park it instead on a couch for the remainder of your transfatty days. Or you can pretend that you don’t even have an ass; pretend that you’re uncloven back there; whatever. Pretend that God didn’t cleave you there.

Go repair a lawnmower, if that’s what empties your sweeper bag. Inject cream into Twinkies with a cream gun, if that’s what wrings your sponge. Call the cream gun “a cream gun,” if that’s what you want to do. Or call it “an orange peeler.” Or call it “a Kirby vacuum cleaner,” I don’t care. Make up whatever euphemism you want for the cream gun. Pretend it doesn’t exist, for all I care. “There are no Twinkies in the world.” Fine. Repeat that like a mantra and fall asleep to it in your own personal twilight, if that’s what forks your hay.

Work on lawnmowers for a living, for all it matters to me. Analyze the different sizes of spark plugs, or whatever. Laud the gasoline engine, for all I care. Work with grease and poop. Catch the poop of cows into a trailer and sling it into fields with automated forks. Write about the spark plugs and call them “spark plugs.” Or call them “gangplanks.” If you’re that removed from reality, why not go ahead and call cow poop, “manure.” Whatever. Whatever it takes to untangle your Slinky, go ahead and do it. Or don’t call the poop anything, if that’s what strains your beets.

Or don’t even write about it. Or don’t write about anything, if that’s what you want. Don’t record anything, for all I care. Leave everything alone, if that’s all you can take. Unhandle the untouchable, if that’s what you can’t touch. Or touch everything. Or don’t touch anything. Or record everything. Or don’t record anything. Or leave everybody to guess, if that’s your God-given bent. Or dip people into their common humanity and make them face it, if that’s what frosts your honey bun. Or become a surgeon and lay out the intestines; somebody named the duodenum, you know. Or join a religion, if that’s what cores your pear.

Do what you will under this great sun of ours because it is imperative that you do so.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

I would not want to be a woman in this life unless I could do it while preserving my male understanding of sex. But neither would I necessarily want to line up with 23,000 other people in Nashville to be segregated into “bins” and walk 13.1 miles over a carpet of paper cups. I love my wife and I need her, just as Jamie needs Larry and Larry needs Jamie. Larry says that Jamie is “so beautiful,” and she is. Jamie is beautiful. But Melody is beautiful, too. The first thing that attracted me to Melody was her eyes, but that was only because the first picture I saw of her framed her neck and head. Had she been framed from the neck down, my eyes would surely have gravitated toward her ass.

My wife has a beautiful ass. It is better than Jamie’s, I think. Does that offend Larry? Does it offend Jamie? Does it offend my readers? Does it offend the Maker of the Female Ass?

My wife has a beautiful ass. It is better than Jamie’s, I think. Does that offend Larry? Does it offend Jamie? Does it offend my readers? Does it offend the Maker of the Female Ass?(It will offend Melody, I'm sure. She did not approve the use of this photograph, and did not pose for the sake of this blog. I talked her into this shot a year and a half ago for inclusion in my marriage book, Shagah. I was studying the waist/hip ratios of women and the effect specific ratios have upon males. Hey. Somebody had to do it. Melody eventually nixed the photo for inclusion in the book, and so did my agent at the time, who was a woman; she was probably jealous. But I'll be darned if this photograph is going to collect dust in a box in the closet.)

No doubt Larry will say that Jamie’s ass is better than Melody’s. That’s fine. Of course he would say that. He must say it. Is it true? I don’t know. I admit that I have not analyzed Jamie’s ass. To do so would be improper. I have a feeling that it's probably terrific. I do not wish to call in an objective party. If I did, I would call my friend Jim. But he thinks that his wife has the best ass, so there you go. To each their own asses.

Or, if you wish, you can choose not to discuss it. Or to appreciate it. Or to write about it. You can go ahead and call your own ass a “hindquarters.” Or “a butt.” Call it "a tush," if you want. You can call it an Oreo, for all I care. You can call birds “women.” You can call women “birds.” You can call chipmunks “birds,” if that’s what hangs your hammock. You can eat lots of food and make your ass grow to the size of a zeppelin, if that’s what you want to do. You can refuse to exercise your God-given ass and park it instead on a couch for the remainder of your transfatty days. Or you can pretend that you don’t even have an ass; pretend that you’re uncloven back there; whatever. Pretend that God didn’t cleave you there.

Go repair a lawnmower, if that’s what empties your sweeper bag. Inject cream into Twinkies with a cream gun, if that’s what wrings your sponge. Call the cream gun “a cream gun,” if that’s what you want to do. Or call it “an orange peeler.” Or call it “a Kirby vacuum cleaner,” I don’t care. Make up whatever euphemism you want for the cream gun. Pretend it doesn’t exist, for all I care. “There are no Twinkies in the world.” Fine. Repeat that like a mantra and fall asleep to it in your own personal twilight, if that’s what forks your hay.

Work on lawnmowers for a living, for all it matters to me. Analyze the different sizes of spark plugs, or whatever. Laud the gasoline engine, for all I care. Work with grease and poop. Catch the poop of cows into a trailer and sling it into fields with automated forks. Write about the spark plugs and call them “spark plugs.” Or call them “gangplanks.” If you’re that removed from reality, why not go ahead and call cow poop, “manure.” Whatever. Whatever it takes to untangle your Slinky, go ahead and do it. Or don’t call the poop anything, if that’s what strains your beets.

Or don’t even write about it. Or don’t write about anything, if that’s what you want. Don’t record anything, for all I care. Leave everything alone, if that’s all you can take. Unhandle the untouchable, if that’s what you can’t touch. Or touch everything. Or don’t touch anything. Or record everything. Or don’t record anything. Or leave everybody to guess, if that’s your God-given bent. Or dip people into their common humanity and make them face it, if that’s what frosts your honey bun. Or become a surgeon and lay out the intestines; somebody named the duodenum, you know. Or join a religion, if that’s what cores your pear.

Do what you will under this great sun of ours because it is imperative that you do so.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Thursday, April 13, 2006

TENDER BABY IN A NEW WOMB: THE HENNESSY ARRIVES

In a flurry of brownness, the UPS man came today with a package so small that it could not have been my hammock. But it was.

I held an impossibly small black bag with white letters on it and a diagram on the back, also in white, showing the proper way to lash my new pet to a tree. I held the bag in my hands and lifted it up and down and up and down, testing its weight. It tested light. I smiled and looked down on my new home. I benedicted it with my eyes. I removed it from its bag. It rewarded me with nylon and mosquito netting and a smell better than that of a new car. I cannot tie knots, however. I have not yet begun, in this life, to lash. So I went to www.hennessyhammock.com to watch a tying/teaching video by someone who used to be or still was a Boy Scout.

You can watch this amazing video for yourself under the section titled “Set-up Instructions.” It is rated “R” for language, violence, and adult situations. You can see for yourself how easy the procedure is. You can see for yourself why it would take a normal person thirty seconds to understand and perfect the procedure. You can see for yourself why it took me an hour to understand and fail to perfect anything near the procedure. Thank God for the pause button. Thank God for rewind. Thank God for the Boy Scouts. Thank God for popcorn and Good ‘N Plenty.

I took my pet to the top of the woods behind our house and lashed it between two trees. I liked it. My pet liked it. The bark of the trees liked the feel of the webbing strap and the tautness of that strap against its rugged skin. The sun and the breeze liked the new smell; they wafted it proudly about the woods and then up toward the tiny puffs of cloud.

I took my pet to the top of the woods behind our house and lashed it between two trees. I liked it. My pet liked it. The bark of the trees liked the feel of the webbing strap and the tautness of that strap against its rugged skin. The sun and the breeze liked the new smell; they wafted it proudly about the woods and then up toward the tiny puffs of cloud.My wife called her friend Jamie when I left the house and they began talking about me. I think my wife is proud of me. I think she is excited for my new hammock and me. I think Jamie respects me. And so I cannot understand why Melody was laughing and whispering. I cannot understand why Jamie was looking out her window with binoculars and laughing as I walked across the field toward our woods. Unable, was I, to interpret what appeared to be Jamie’s mirth.

The bottom of the hammock has a slit running halfway up its length. I poked my head through that, sat down toward the back of the hammock, pulled in my feet, and that was it. I was in. I was in the Hennessy Hammock. The entrance Velcroed itself closed behind me and every mosquito in the woods became instantly stymied. I, myself, became ensconced in nylon and netting. The trees benedicted me with their eyes, and bravely sustained my weight.

Do not ever laugh at—or artificially magnify—a tender baby in the new womb.

Do not ever laugh at—or artificially magnify—a tender baby in the new womb.© 2006 by Martin Zender

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

TO BE A DUCK

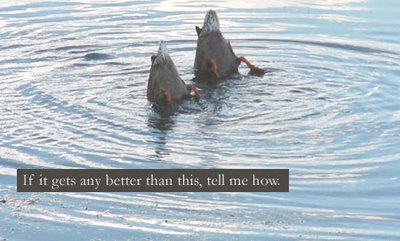

I told you some time ago that if I could be any animal, I would be a duck. I told you that someday I would tell you why.

I do not like where my eyes are. I want eyes at the sides of my head. And I want black eyes the size of small marbles. But what I want most of all is a bill.

I want an orange bill. A bill is what I want, and it must be orange. I want a bill with which to eat and preen. I would let people call my bill “a bill,” but never a beak. Never a beak, or “a hard nose,” “a preening blade,” or “a saw-toothed nibbler.”

My bill will look so fine beneath my small, duck-shaped skull. The best part about billdom is the purposeful expulsion of quacks from it. All the livelong day: expulsing purposeful quacks.

My bill will look so fine beneath my small, duck-shaped skull. The best part about billdom is the purposeful expulsion of quacks from it. All the livelong day: expulsing purposeful quacks.

The greatest noise in the kingdom of animals is the quack. It comes from the bill of the duck, and nothing else. The word itself is worth a fortune: quack. It is spelled like it sounds and is savory. I would quack all day. The quack is rich and self-explanatory. Every answer to every question, statement, or quotable quote, would—from me—be a quack.

“How is it, really, being a duck?”

“Quack.”

“What does a woman want?”

“Quack.”

“You know your house payment is due.”

“Quack.”

“Seventy more soldiers died in Iraq.”

“Quack.”

“These are the times that try men’s souls.”

“Quack.”

“Your nostrils are in your bill, evenly distributed.”

“Quack.”

“It’s time to save the planet.”

“Quack.”

“Your bill is not a preening blade.”

“Quack.”

“How much money do you have?”

“Quack.”

“You’re kind of cute.”

“Quack.”

“From your bill are expulsed many and purposeful quacks.”

“Quack-quack.”

“Are you warm and dry?”

“Quack.”

“This pond is drying up.”

“Quack.”

“Quel heur est'il?”

“Quack.”

“Simplify.”

“Quack-quack.”

“I know people at the pellet company.”

“Quack.”

“The sun will blow up in a million and sixty years.”

“Quack-quack.”

I would quack (and quack) all the livelong day.

As I duck, I could do it all. I could and I would do: it all. I would swim and fly and walk. When I wanted to walk, I would walk out of the pond and walk. When I wanted to swim, I would walk into the pond and swim. When I wanted to fly, I would fly out of the pond and fly. Or I would walk out of the pond and fly. Or I would fly out of the pond and walk. Or I would swim out of the pond and walk and fly.

The best part about flying would be landing in the pond. I would coast to the pond and backpedal with my wings to land with a green and foamy splash in the pond. The landing would be soft and nearly silent. Then I would just paddle around like it was nothing to me, which it would be. Unknown, to me, would the wiles of fatigue be. I would take off and land in a foamy splash and paddle the circumference of the pond looking sprightly—a hundred times a day. People would throw me pellets. I would consume pellets like a nibbler. I would land for pellets and walk for the littlest nibble. I would walk on my webbed feet toward the weedy-colored food.

I want webbed feet that are orange. My feet must match my bill. I would invite the masses to touch my marvelous webbing.

“We will throw you pellets if we may touch your webbing.”

“Quack.”

“The webbing is marvelous to touch. No other duck lets us touch it.”

“Quack.”

“You’re kind of cute.”

“Quack.”

“You are such a unique duck.”

“Quack.”

”We want to be you.”

“Quack-Quack.”

The two best parts about being a duck would be 1) the location and placement of my nostrils on my bill, and 2) my willingness and ability to stick my butt in the air out of the water, very high, while the rest of me is underwater searching for food or simply letting people see my orange, webbed feet paddling hard to keep my butt in clear view of everyone while I open my black marble eyes underwater and look through the murkiness at anything I want to, including the people who see my smooth butt so high up in the air, and how the water runs down my smooth butt, and how my legs match my feet that match my bill which works so hard quacking underwater and making bubbles come up until I fly away when I want to at a right sprightly clip.

The two best parts about being a duck would be 1) the location and placement of my nostrils on my bill, and 2) my willingness and ability to stick my butt in the air out of the water, very high, while the rest of me is underwater searching for food or simply letting people see my orange, webbed feet paddling hard to keep my butt in clear view of everyone while I open my black marble eyes underwater and look through the murkiness at anything I want to, including the people who see my smooth butt so high up in the air, and how the water runs down my smooth butt, and how my legs match my feet that match my bill which works so hard quacking underwater and making bubbles come up until I fly away when I want to at a right sprightly clip.

Oh, to be a duck.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

I do not like where my eyes are. I want eyes at the sides of my head. And I want black eyes the size of small marbles. But what I want most of all is a bill.

I want an orange bill. A bill is what I want, and it must be orange. I want a bill with which to eat and preen. I would let people call my bill “a bill,” but never a beak. Never a beak, or “a hard nose,” “a preening blade,” or “a saw-toothed nibbler.”

My bill will look so fine beneath my small, duck-shaped skull. The best part about billdom is the purposeful expulsion of quacks from it. All the livelong day: expulsing purposeful quacks.

My bill will look so fine beneath my small, duck-shaped skull. The best part about billdom is the purposeful expulsion of quacks from it. All the livelong day: expulsing purposeful quacks.The greatest noise in the kingdom of animals is the quack. It comes from the bill of the duck, and nothing else. The word itself is worth a fortune: quack. It is spelled like it sounds and is savory. I would quack all day. The quack is rich and self-explanatory. Every answer to every question, statement, or quotable quote, would—from me—be a quack.

“How is it, really, being a duck?”

“Quack.”

“What does a woman want?”

“Quack.”

“You know your house payment is due.”

“Quack.”

“Seventy more soldiers died in Iraq.”

“Quack.”

“These are the times that try men’s souls.”

“Quack.”

“Your nostrils are in your bill, evenly distributed.”

“Quack.”

“It’s time to save the planet.”

“Quack.”

“Your bill is not a preening blade.”

“Quack.”

“How much money do you have?”

“Quack.”

“You’re kind of cute.”

“Quack.”

“From your bill are expulsed many and purposeful quacks.”

“Quack-quack.”

“Are you warm and dry?”

“Quack.”

“This pond is drying up.”

“Quack.”

“Quel heur est'il?”

“Quack.”

“Simplify.”

“Quack-quack.”

“I know people at the pellet company.”

“Quack.”

“The sun will blow up in a million and sixty years.”

“Quack-quack.”

I would quack (and quack) all the livelong day.

As I duck, I could do it all. I could and I would do: it all. I would swim and fly and walk. When I wanted to walk, I would walk out of the pond and walk. When I wanted to swim, I would walk into the pond and swim. When I wanted to fly, I would fly out of the pond and fly. Or I would walk out of the pond and fly. Or I would fly out of the pond and walk. Or I would swim out of the pond and walk and fly.

The best part about flying would be landing in the pond. I would coast to the pond and backpedal with my wings to land with a green and foamy splash in the pond. The landing would be soft and nearly silent. Then I would just paddle around like it was nothing to me, which it would be. Unknown, to me, would the wiles of fatigue be. I would take off and land in a foamy splash and paddle the circumference of the pond looking sprightly—a hundred times a day. People would throw me pellets. I would consume pellets like a nibbler. I would land for pellets and walk for the littlest nibble. I would walk on my webbed feet toward the weedy-colored food.

I want webbed feet that are orange. My feet must match my bill. I would invite the masses to touch my marvelous webbing.

“We will throw you pellets if we may touch your webbing.”

“Quack.”

“The webbing is marvelous to touch. No other duck lets us touch it.”

“Quack.”

“You’re kind of cute.”

“Quack.”

“You are such a unique duck.”

“Quack.”

”We want to be you.”

“Quack-Quack.”

The two best parts about being a duck would be 1) the location and placement of my nostrils on my bill, and 2) my willingness and ability to stick my butt in the air out of the water, very high, while the rest of me is underwater searching for food or simply letting people see my orange, webbed feet paddling hard to keep my butt in clear view of everyone while I open my black marble eyes underwater and look through the murkiness at anything I want to, including the people who see my smooth butt so high up in the air, and how the water runs down my smooth butt, and how my legs match my feet that match my bill which works so hard quacking underwater and making bubbles come up until I fly away when I want to at a right sprightly clip.

The two best parts about being a duck would be 1) the location and placement of my nostrils on my bill, and 2) my willingness and ability to stick my butt in the air out of the water, very high, while the rest of me is underwater searching for food or simply letting people see my orange, webbed feet paddling hard to keep my butt in clear view of everyone while I open my black marble eyes underwater and look through the murkiness at anything I want to, including the people who see my smooth butt so high up in the air, and how the water runs down my smooth butt, and how my legs match my feet that match my bill which works so hard quacking underwater and making bubbles come up until I fly away when I want to at a right sprightly clip.Oh, to be a duck.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Saturday, April 08, 2006

LAST LAUGH IN AMISH COUNTRY

I walked 32 miles last Sunday, 21 of it through Amish country. I have a fantasy about Amish women, thanks for asking. I imagine that they are all sexually repressed and ready to blow. All my fantasies are duds, however. When the pin is finally pulled, none of my fantasies ever explode. If you want the truth of a thing, analyze my fantasies and believe the opposite. The truth of this Amish matter, therefore, is that Amish women are happily asexual and ready to weave a blanket.

I walked 32 miles last Sunday, 21 of it through Amish country. I have a fantasy about Amish women, thanks for asking. I imagine that they are all sexually repressed and ready to blow. All my fantasies are duds, however. When the pin is finally pulled, none of my fantasies ever explode. If you want the truth of a thing, analyze my fantasies and believe the opposite. The truth of this Amish matter, therefore, is that Amish women are happily asexual and ready to weave a blanket.I passed through a small town, Vicksburg, named after the historic Civil War battle. The town was old enough, I believe, to have known the smell of gunpowder. Walking through, I expected to see General Lee himself galloping out of the morning mist. Hand-painted lettering on one of the wooden buildings said, “D.W. Coburn, Horseshoer.” Coburn, no doubt, fought for the Union. At this early hour, he was probably still in bed.

I sipped some Gatorade from my drinking tube and slapped myself back into the 21st century. Turning a corner out of town and heading north on Gimbly Road, a string of Amish buggies came down a hill toward me at two-hundred yard intervals. If you have never seen such a thing, you should. It’s a postcard on a squeaky iron rack in a sausage-scented restaurant. The sight slapped me back into 1865, only this time I expected John Wilkes Booth to hobble from a barn.

I sipped some Gatorade from my drinking tube and slapped myself back into the 21st century. Turning a corner out of town and heading north on Gimbly Road, a string of Amish buggies came down a hill toward me at two-hundred yard intervals. If you have never seen such a thing, you should. It’s a postcard on a squeaky iron rack in a sausage-scented restaurant. The sight slapped me back into 1865, only this time I expected John Wilkes Booth to hobble from a barn.I waved to the occupants of the buggies as they passed. I saw some of their faces. Who were these people? I considered jumping into one of the buggies: “Who are you people?” I would mount the vehicle, nudge open the door, snuggle in beside the happy (?) couple and begin querying them, beginning with the woman.

“Excuse me, ma’am. Are you sexually repressed? Don’t mind me, I’ve just always wondered. Oh, hello sir, yes, thank you for hitting me. I thought you were all pacificists, but I see that another Amish fantasy of mine has failed to detonate. May I have a word with your wife? That hurt, you know. My name is Martin Zender. Hello, ma’am. You are happily asexual, I presume. Is this your blanket?”

But I only waved. One young man wore round glasses and was laughing. The man was laughing. What was he laughing at? What else but me? He and his wife no doubt found humor in my Amish fantasies. Are they that transparent, my fantasies? They must be. The horses clopped toward church, I knew. If the riders were to laugh at all this day, now was the time. Chuckles, at church, get buggy-whipped to the sod, where the pews are screwed in and the hobnailed boots of the congregants scuffle. It was now or never, and here was the opportunity: a stupid-looking walker with hilarious Amish fantasies. Oh, they were laughing at me, all right.

When the last of the buggies passed, the bell of a distant church tolled. It tolled again and again—for me, I knew. It sent a shiver down me. It was now 1837 and the rote of a dark tradition overcame me. I had to get out before General Washington showed up. Or worse, a contingent of the British.

I stopped for a break at an old cemetery and sat down to put my back against the wire fence and eat an orange. A car went by. Then two. Then three. I peeled a sticker from the orange that said, “Sunkist.” Slowly came the world again, the one I had known. Straining, I could no longer hear the church bell, or the clop of a single horse. I got up and stared for a long time, behind me, at the crumbled stones. Beneath these markers, they all lay still. Not a soul laughed. I was humbled and ashamed of myself. They had all once heard the bell that had tolled so recently for me. I strained in my mind’s eye to see the Amishman again. I would not be so rude this time. I would bow, courteously, to his beautiful wife. He was laughing at me, yes—at me and my time.

To some, there is no time, and these are the Amish, the church bells, and the citizens of the grave.

To some, there is no time, and these are the Amish, the church bells, and the citizens of the grave.And the only ones of these three able to laugh, do so.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

A BROTHERHOOD OF CREEPIES

I used the money from my tax refund to order the Hennessy hammock. What a day it will be when the Hennessy arrives. I’ll be waiting for the UPS man like I used to wait for the mailman when I ordered X-Ray glasses from comic books and the “super magnifying” telescope from Cap’n Crunch cereal.

I used the money from my tax refund to order the Hennessy hammock. What a day it will be when the Hennessy arrives. I’ll be waiting for the UPS man like I used to wait for the mailman when I ordered X-Ray glasses from comic books and the “super magnifying” telescope from Cap’n Crunch cereal.The idea of stealth camping is growing on me. I like the idea of never again paying twenty bucks at a crowded, noisy campground for the privilege of leasing patches of sod infested with sticks and rocks. On my daily eight-mile walks I see beautiful woods with straight, tall trees that I would rate as highly hammockable. I pretend that I am coming upon them on my walk to Pittsburgh. But there are large yellow signs on many of the trees in front of some of these woods, and these signs say, NO HUNTING, NO TRESPASSING. I ask myself what I will think when I see signs like these on the walk to Pittsburgh. I answer myself: I will think, thank God that I will not be bothered by either hunters or trespassers this evening.

At first, the thought of sneaking into a woods at dusk to spend the night alone hanging between two trees creeped me out. But then I realized that I was on the good end of the Creep Factor. I will be the creepy one. It has been my theory since embarking upon self-propelled adventure thirty-three years ago that creepy people leave other creepy people alone. We creepies are a brotherhood, you see. We only creep other people out, never ourselves. We creep out people who live the whole of their lives avoiding creephood at all cost. (This includes most people.)

I plan, on the Pittsburgh walk, to enter the woods at dusk and vacate before dawn. Let’s say there is a person walking down a country road in Pennsylvania at 5:30 a.m. Suddenly, the person hears something large wandering out of the woods, and that something is clearing its throat. Now, which phantom of the dawn will be wetting pants, the one on the road, or the one emerging from the woods?

On one of my eight-mile training walks last week, I walked into a woods off Route 9. I’d had my eye on this tract for weeks, pegging it as a good one to hang in for practice. I had yet to order my hammock, but I wanted to scout this potential campsite in broad daylight, just to see what would happen. I wanted to pretend to be on the Pittsburgh walk, just to see how it would feel to duck into a cluster of someone else’s trees.

The nearest house was three hundred yards away. I waited for a lull in the traffic, then walked in. I went in twenty-five yards, found two beautiful trees spaced perfectly apart, and stood there. There were no alarms, no dogs, no cops. Holy cow, I said to myself, this will be easier than I thought. I pretended to tie my hammock to the trees. The woods felt so peaceful; cars swished by on the highway; I took a leisurely leak. I watched the drivers’ heads through the trees, to see if any were looking at my leak. None of them looked at the leak, not one. Why would they? “Oh. Harold. I’m going to check all the woods between here and Broomsfield to see if there might be anyone hammocking in them—or possibly leaking.”

The nearest house was three hundred yards away. I waited for a lull in the traffic, then walked in. I went in twenty-five yards, found two beautiful trees spaced perfectly apart, and stood there. There were no alarms, no dogs, no cops. Holy cow, I said to myself, this will be easier than I thought. I pretended to tie my hammock to the trees. The woods felt so peaceful; cars swished by on the highway; I took a leisurely leak. I watched the drivers’ heads through the trees, to see if any were looking at my leak. None of them looked at the leak, not one. Why would they? “Oh. Harold. I’m going to check all the woods between here and Broomsfield to see if there might be anyone hammocking in them—or possibly leaking.”I was good to go in more ways than one.

My only other concern was the critters of the woodlands. I like animals, but I do not want eaten by one. In this part of the country, however, there are few man-eating beasts afoot. There are, however, beasts that walk through the woods at night and make twigs snap. They scurry and forage and snap twigs, these beasts, and I do not want to hear them. Of course it’s a deer or a possum or a raccoon—but what if it isn’t?

My son Jefferson and I were in the car one evening when the car started making a strange noise. “What’s that noise, Dad?” asked Jefferson.

“I have no idea, son,” I said. “You may as well be asking me for the secret of the universe. But actually, I do know the secret of the universe. But cars and engines? Sorry.”

Still, I could not let the opportunity pass to offer fatherly wisdom to my son. “Whenever your car starts making noises, do what I do,” I said.

“What’s that, Dad?”

“Turn up the radio.”

I plan on applying the same principle to the problem of snapping twigs: I will wear the best pair of foam earplugs money can buy.

Everything is now in order, all problems solved. And so, Come quickly, UPS man.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

WITH A BUTLER ON THE LADDER AND A PHIPPS IN HAIR

I was driving my thirteen year-old son Jefferson home from baseball practice yesterday when we (I) decided to flick on a classic rock station. On came Led Zeppelin’s Livin’, Lovin’ Maid. Did that ever bring back memories. Naturally, I had to tell Jefferson about the time I lip-synched the song in front of my entire fourth grade class while wearing green and white checkered pants, a yellow shirt, a Daniel Boone vest, saddle shoes, eating a cherry Tootsie Pop—which served as my microphone—and guessing madly at the lyrics. I hope I did not make a mistake confiding this indiscretion to my youngest son. Jefferson left home this morning with a bag tied to a stick slung across his shoulder, so when he returns home (if he does), I will ask him.

The year was 1969. The occasion was a fourth grade lip-synching contest. What sort of manic teacher would conduct such a competition, and for what purpose, I do not know. But now, in a bout of remembrance, I do know. It was the infamous Miss Clouse.

I remember the day Miss Clouse first walked into our classroom. Actually, she ran. She was late, and our first vision of her was of mincing red heels. She had hair that rose above her forehead in a That Girl pompadour. The hair was Harlow gold, however. Lips: Sweet Surprise. Her hands were always cold; she had Rumplestiltskin eyes.

Each student was to bring a record and be prepared to humiliate him or herself to it. Miss Clouse was the Mistress of Lasting Embarrassment and stood ready at the turntable. Today, I hope it was worth it to her. I hope, at least, that her children are unharmed by the events of that unforgettable afternoon.

Classmates before me did acts like The Rhonettes. They lip-synched to singers like Bobby Darrin and The Everly Brothers. One crazy kid did Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue.” He wore Buddy Holly-style glasses but he looked ridiculous in them because he weighed two hundred pounds and his head was the size of a Swiss exercise ball. He did the “…Peggy Sue-a-hoo, hoo-hoo-a-hoo-hoo” part, and everyone laughed. Everyone thought it was ridiculous. But no one had seen ridiculous yet.

My aforementioned clothes (the pants, the jacket, the shoes) were not only a part of my act, they were part of my regular school attire. For me, every day was an act.

My aforementioned clothes (the pants, the jacket, the shoes) were not only a part of my act, they were part of my regular school attire. For me, every day was an act.

I had begged my mother to buy me the green and white checkered pants. Something about the pants reflected my soul at the time (it was my Green and White Checked period), and I wished to display that to the world. My mother, however, wanted denim for me. Her idea of normal was blue jeans. This clashed impossibly with my idea of normal, which was green and white checks. My mother said, “Why don’t you want to wear a regular pair of pants like a normal boy?” I answered that normal-boy clothes did not reflect the current state of my soul. Mother had no answer for that, so she bought me the pants. Winning this argument was easy compared to the time I wanted saddle shoes—that battle took time.

“Saddle shoes are for girls,” my mother said.

“Not really,” I said. “I saw a picture of Uncle Jim in saddle shoes. He’s a famous writer and he lives in Hollywood.”

“Your Uncle Jim is strange.”

“What if I’m the artsy type?”

“Then I’ll probably have to take you to a psychiatrist.”

“Oh, look! Here’s a swell pair of saddle shoes. And they have my size!”

My mother bought me the shoes and I became the talk of the class. I was obviously a trend-setter. It was not my fault that no one followed my trends. At least I started conversations. I got people to thinking. Kids actually wanted to be seen with me. I was a ten year-old Happening.

I got the Daniel Boone jacket at the Myers Lake Shopping Plaza. A

men’s clothing store there was giving them away. In fact, they were giving people a quarter to take one. Once again, my poor mother was at my side. I said, “Look, Mother! They’re giving away Daniel Boone jackets! In fact, they’re paying people a quarter to take one. Have you ever seen a sale as crazy as this one? Have you? Look at the cool fringe hanging off the jackets! I sure wish I had one of those. I could settle Kentucky in one of those things. Can you imagine how I would look in that Daniel Boone jacket and my checkered pants, and my saddle shoes? Why are you stopping? Mother, are you getting dizzy? Look! That man is handing us a quarter!”

The shirt I procured later was the color of the Beatles’ submarine, only yellower.

The Swiss ball kid sat down to resume his life of doom, and it was my turn. Miss Clouse dropped the needle on my 45, and I was off to another world. It was a good world. I liked the world.

Most of my classmates still remember my performance. For some, it was a pivotal moment in their lives. One has since said, “Martin, when I saw you do Livin’, Lovin Maid, it opened doors for me. I realized then that anything was possible. You were outside yourself; it was like you had no self-consciousness, none at all. None of the things that normally hold people back affected you that day. And you kept eating that sucker! It was the way you ate it. And how you licked it like a lunatic at the end when Robert Plant does that crazy thing with the ‘L’s.’” My friend got teary. “You changed my life, man.”

But it was another boy who gave me the “thumbs up,” through the glass, as I sat alone in the principal’s office.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

The year was 1969. The occasion was a fourth grade lip-synching contest. What sort of manic teacher would conduct such a competition, and for what purpose, I do not know. But now, in a bout of remembrance, I do know. It was the infamous Miss Clouse.

I remember the day Miss Clouse first walked into our classroom. Actually, she ran. She was late, and our first vision of her was of mincing red heels. She had hair that rose above her forehead in a That Girl pompadour. The hair was Harlow gold, however. Lips: Sweet Surprise. Her hands were always cold; she had Rumplestiltskin eyes.

Each student was to bring a record and be prepared to humiliate him or herself to it. Miss Clouse was the Mistress of Lasting Embarrassment and stood ready at the turntable. Today, I hope it was worth it to her. I hope, at least, that her children are unharmed by the events of that unforgettable afternoon.

Classmates before me did acts like The Rhonettes. They lip-synched to singers like Bobby Darrin and The Everly Brothers. One crazy kid did Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue.” He wore Buddy Holly-style glasses but he looked ridiculous in them because he weighed two hundred pounds and his head was the size of a Swiss exercise ball. He did the “…Peggy Sue-a-hoo, hoo-hoo-a-hoo-hoo” part, and everyone laughed. Everyone thought it was ridiculous. But no one had seen ridiculous yet.

My aforementioned clothes (the pants, the jacket, the shoes) were not only a part of my act, they were part of my regular school attire. For me, every day was an act.

My aforementioned clothes (the pants, the jacket, the shoes) were not only a part of my act, they were part of my regular school attire. For me, every day was an act.I had begged my mother to buy me the green and white checkered pants. Something about the pants reflected my soul at the time (it was my Green and White Checked period), and I wished to display that to the world. My mother, however, wanted denim for me. Her idea of normal was blue jeans. This clashed impossibly with my idea of normal, which was green and white checks. My mother said, “Why don’t you want to wear a regular pair of pants like a normal boy?” I answered that normal-boy clothes did not reflect the current state of my soul. Mother had no answer for that, so she bought me the pants. Winning this argument was easy compared to the time I wanted saddle shoes—that battle took time.

“Saddle shoes are for girls,” my mother said.

“Not really,” I said. “I saw a picture of Uncle Jim in saddle shoes. He’s a famous writer and he lives in Hollywood.”

“Your Uncle Jim is strange.”

“What if I’m the artsy type?”

“Then I’ll probably have to take you to a psychiatrist.”

“Oh, look! Here’s a swell pair of saddle shoes. And they have my size!”

My mother bought me the shoes and I became the talk of the class. I was obviously a trend-setter. It was not my fault that no one followed my trends. At least I started conversations. I got people to thinking. Kids actually wanted to be seen with me. I was a ten year-old Happening.

I got the Daniel Boone jacket at the Myers Lake Shopping Plaza. A

men’s clothing store there was giving them away. In fact, they were giving people a quarter to take one. Once again, my poor mother was at my side. I said, “Look, Mother! They’re giving away Daniel Boone jackets! In fact, they’re paying people a quarter to take one. Have you ever seen a sale as crazy as this one? Have you? Look at the cool fringe hanging off the jackets! I sure wish I had one of those. I could settle Kentucky in one of those things. Can you imagine how I would look in that Daniel Boone jacket and my checkered pants, and my saddle shoes? Why are you stopping? Mother, are you getting dizzy? Look! That man is handing us a quarter!”

The shirt I procured later was the color of the Beatles’ submarine, only yellower.

The Swiss ball kid sat down to resume his life of doom, and it was my turn. Miss Clouse dropped the needle on my 45, and I was off to another world. It was a good world. I liked the world.

Most of my classmates still remember my performance. For some, it was a pivotal moment in their lives. One has since said, “Martin, when I saw you do Livin’, Lovin Maid, it opened doors for me. I realized then that anything was possible. You were outside yourself; it was like you had no self-consciousness, none at all. None of the things that normally hold people back affected you that day. And you kept eating that sucker! It was the way you ate it. And how you licked it like a lunatic at the end when Robert Plant does that crazy thing with the ‘L’s.’” My friend got teary. “You changed my life, man.”

But it was another boy who gave me the “thumbs up,” through the glass, as I sat alone in the principal’s office.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Saturday, April 01, 2006

CURLICUES OF A WICKED EON

My oldest son Artie and I went out this late afternoon to film depressing scenes for an edition of ZenderFilms. Depressing scenes are so easy to come by here. All one need do, really, is aim the camera any old where and press the record button. But Artie and I wanted to create something. He is a filmmaker, I am writer; we would put our heads together—and probably get them wet: it was raining.

My oldest son Artie and I went out this late afternoon to film depressing scenes for an edition of ZenderFilms. Depressing scenes are so easy to come by here. All one need do, really, is aim the camera any old where and press the record button. But Artie and I wanted to create something. He is a filmmaker, I am writer; we would put our heads together—and probably get them wet: it was raining.Have I told you about ZenderFilms? Looking back now, I see that I haven’t. I want to create a series of video vignettes that will teach small but monumental kernels of scriptural truth. I’m talking eight to ten minute episodes in the reality television vein.

One of the pieces I have in mind is a series of depressing, outdoor shots, accompanied by a somber voiceover (mine) describing the nature of this current wicked eon. Evolution? No, my friends. The earth is in a state of de-volution, and so many things in this world conspire to take us down with them. The piece will teach the futility of certain brands of human escape, while heralding the benefit of others, such as sleep. Eight hours of sleep, you know, is a pearl of great price to me, and one of the most gracious gifts bestowed by God upon the sons and daughters of humanity.

My son is a serious filmmaker and has invested in a $3,500 video camera. He was afraid of getting it wet, so insisted I take an umbrella and hold it over him while he shot. I was happy to do it. I loved this idea of us being a film crew. It was only him and me, but that counted as a crew to me. Off we went to make something out of nothing.

The process of creation thrills me. I was born to create; God planted a small piece of godhood in my breast. To make an abstraction concrete touches sensitive chords beneath my rib cage. The artist has a thought, or a dream, or a lesson to teach. He or she perceives, in one moment, a sliver of universal truth. But, like the primordial earth, it is without form and void. It is invisible. This light of revelation exists only in the head or the heart or the soul of the one chosen by God to articulate it. The things exist now only in the way the artist’s hand shakes, or in the way the heart beats, or in the way the artist sees light where no light is, or shadows where light washes everything.

The challenge and the torture of the artist is the God-imposed necessity to bring forth into concrete existence the abstract thought. Even God records truth for human consumption. Truth, to be appreciated, needs seen, or heard, or read, or touched. God mercifully provides the media. This media is dug from quarries, or mined, or ground into pigments, or stripped from the bark of trees, or fashioned into hollow pieces of wood. If the artist is a sculptor and the medium is marble or clay, the truth takes three-dimensions. If the artist is a musician and the medium is music, the truth speaks via certain notes played a certain way in a certain order at a certain time. The art not only resides in the notes, but in the inspired spaces between them. A piano keyboard articulates one truth, a violin another, a human voice yet another. If the artist is a painter or photographer, he or she captures a moment of time with pigment, with color drawn from the earth’s native hues, or with light on loan from the sun. The filmmaker captures moving images. The writer places letters side-by-side, in the right order, at the right time, cajoling the letters, belaboring them, marching them en masse toward a desired effect.

As we set out, I felt large. Artie and I were gods. Yes. Small ‘g’ gods, enabled by the capital “G” God, graced with a mood-capturing medium, energized by the goal of bringing His light to the world. What was this but a fresh crack at Eden? It was a means of rectifying the temporary desecration of man.

We began at a place on my walking route where a county crew hacked away at a new bridge. It was Saturday afternoon, however, and the crew was gone. But there was plenty of mud, plenty of grease-soaked chains, plenty of brown watergurgles running nowhere.

Near the site, a trio of gray gain silos rose above a farm through the mist and into the gray sky. “Let’s get that,” I told Artie, and we hopped from the car. I extended the umbrella while Artie’s medium recorded an eonian moment headed for the past. The silence was somber and holy. The silos and the silence, and my son and I—these things impressed me. God was teaching me a lesson about the wicked eon.

We filmed odd tree branches, some weeds, and some slabs of concrete from the unfinished bridge. It was growing dark. Satisfied with our work, we headed home. On the way down our road, the property of a neighbor suggested itself.

We filmed odd tree branches, some weeds, and some slabs of concrete from the unfinished bridge. It was growing dark. Satisfied with our work, we headed home. On the way down our road, the property of a neighbor suggested itself.“Stop here,” I said to Artie. “Let’s get that.”

“They’re our neighbors,” he said. “What if they see us?”

I had to think about that one.

“We’ll tell them, ‘Please excuse us. We are filmmakers looking for depressing, broken-down garbage typical of an evil eon, and your property provided us a cornucopia of opportunity.’”

Artie laughed. I laughed. We took three shots and drove the short distance home. Melody had hot chocolate on the stove. The curling swirls of steam rising from the pan of chocolate spoke a new language. It was a new form of art I had not considered before. I stared at it. The steam went to heaven in curlicues, then disappeared.

It went to heaven in curlicues, then disappeared.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)