In case you do not know it, today is National Drilling Day in Bosnia. This is a Bosnian holiday only. Only in Bosnia do people celebrate this day. People in Bosnia will be drilling today, you can bet that. And not only dentists, mineworkers and army sergeants, but everyone. Everyone will be drilling something, even if it is only a 52-foot well.

If this day is not marked on your calendar, then you must return your calendar to its place of purchase for a full refund, demanding that no questions be asked. Tell the vendor: “I am returning this calendar because it has failed to alert me to National Drilling Day. You see? I am now pointing to the twenty-first of April, and it is nothing but an empty white square with nothing written in it except the number ‘21.’ Does this seem right to you? Does it seem thorough enough for me? Does it seem politically correct to anyone? Shah! Do not even think of asking a question! A globally aware person such as myself must be kept abreast of the ways of other peoples and their ceaseless miseries, and not merely of the phases of the moon or when Canadians celebrate Thanksgiving.”

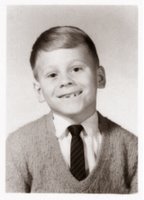

National Drilling Day did not become a recognized holiday until 1986, which is why I did not know about it as a third-grader at Saint Bernadette School of the Burned Martyrs in 1968. For it was then that I began The Martin Zender Drilling Company.

The Martin Zender Drilling Company consisted of me, a pencil, and a desk. I remember the day I began The Great Hole. I gently sat the sharpened point of a number two lead pencil against the surface of my wooden desk. I held it there between my two palms like a Saturn V rocket poised for the moon between two giant palms. But instead of launching it, I began rolling my “rocket” back and forth between my palms in the manner of an upright lathe. That’s how it all began.

The Martin Zender Drilling Company consisted of me, a pencil, and a desk. I remember the day I began The Great Hole. I gently sat the sharpened point of a number two lead pencil against the surface of my wooden desk. I held it there between my two palms like a Saturn V rocket poised for the moon between two giant palms. But instead of launching it, I began rolling my “rocket” back and forth between my palms in the manner of an upright lathe. That’s how it all began.I told my friend Brian Malinowski, who was seated next to me, “See here, Brian. See here what I’m doing. See what a genesis is here. I am beginning a hole, Brian, but not just any hole. No, but this is to be The Great Hole. Are you comprehending it? From the looks of you, I must wonder. Shake yourself from the stupor of unbelief! Comprehend the era! For in less than two months, I shall have drilled through this entire desk. And yet this is the beginning of it—right now. You are here to see it, to witness the inauguration of it. This is bigger than Lincoln’s speech at Valley Forge.”

I paused to look around me. Mrs. Ditchwald busied her silly self writing ridiculous-looking numbers on the blackboard. All the other students were either minding the numbers or dreaming of bologna sandwiches. The clock clicked another minute into my promising future while a strange gaseous residue hissed from the coils of a green-silver nozzle on the bottom coils of the heater thing by the window. I lowered my voice. “It is not an auspicious beginning, Brian, I grant you that. But it will be auspicious when you see the results two months from now.”

Each day I patiently drilled The Great Hole. I drilled and I drilled. Brian Malinowski told other students about it, and they all came by at different times to witness my progress. Some whistled in awe. Others asked to see my pencil. “You mean my drill?” I would say. Most classmates had at least some hazy notion of my genius. Others openly acknowledged it. More importantly, each and sundry admired my spunk and pluck. One girl even said to me, “Martin, I admire your spunk and pluck.”

Each day I patiently drilled The Great Hole. I drilled and I drilled. Brian Malinowski told other students about it, and they all came by at different times to witness my progress. Some whistled in awe. Others asked to see my pencil. “You mean my drill?” I would say. Most classmates had at least some hazy notion of my genius. Others openly acknowledged it. More importantly, each and sundry admired my spunk and pluck. One girl even said to me, “Martin, I admire your spunk and pluck.”Fortunately for me, it was at this precise juncture that I required a secretary.

“Kelly McGowan,” I said. “You are an extremely intelligent girl. And you wear pastel-colored skirts several inches above your knees. Better legs, I have never seen.”

“And you are Martin Zender,” she said. “Driller of Holes and Failer of Math.”

“Driller of The Great Hole,” I corrected. We both looked down at my speedily-rotating drill, and at the considerable sawdust accumulating faster than Kelly’s puckered, red lips could blow it away. “It’s coming along,” I said. “But things are getting complicated now.” I tried to sound grim and optimistic simultaneously. “This is week three. I’m still five weeks away from blasting through this puppy. But I’m finding it hard to drill and at the same time mentally write my next screenplay. Do you understand what I’m telling you?”

“No.”

“It’s a strain on me, Kelly, to push The Juggernaut of Creativity, along with this pencil. It’s all metaphoric, I fear. I fear I may be going mad. It’s getting to be too much for one man. I’m only human here.”

“What are you saying, Martin?”

“I’m saying that—Would you like to be secretary of The Zender Drilling Company?”

Kelly blushed from the tip of her auburn hair to the frill on her little white socklets. It was so gratifying to see. “I am looking for part-time work,” she said. She looked down and blushed even more. “I do appreciate what you’re doing, Martin. I believe in you.” Without warning, her head snapped up. “Do I have to take dictation?”

Kelly blushed from the tip of her auburn hair to the frill on her little white socklets. It was so gratifying to see. “I am looking for part-time work,” she said. She looked down and blushed even more. “I do appreciate what you’re doing, Martin. I believe in you.” Without warning, her head snapped up. “Do I have to take dictation?”I put down my drill and lit a cigarette. “No. I only need you to file reports. I may need you for publicity. You’ll have regular hours and full benefits, I promise.”

“Paid maternity leave?”

“Of course. I’m covered for that.”

She looked down again. “It’s just that things happen.”

“Kelly. I know. Forget it. I already told you: paid maternity leave.”

“What about holidays?”

I put the top of a crooked index finger beneath her pretty chin and brought her head up to look at me. “Never, Kelly. Do you hear me? I promise. Not one holiday, not even St. Francis of Assisi Adopt a Sick Bird Day.”

Kelly let a smile escape her luscious lips. “Okay, Martin. I’ll do it. I want to do it. I think about you all the time. I believe in you. I believe in what you’re doing. I’ve always been fatally attracted to boys like you.” I had a good command of the bottom of her chin, so Kelly looked over at The Great Hole with her eyes only. “I think you can finish this in four weeks, if you put your mind to it. But listen. You have got to promise me that you won’t let a word of this slip to Mrs. Ditchwald.”

I let go of Kelly’s chin, rolled my own eyes, and flicked a long ash from my cigarette seventeen feet into a golden watering can, where it hissy-fitted out. “C’mon, Kelly. The success of this whole project depends on Ditchwald’s ignorance. But why would she even care about The Great Hole? Look at her.”

We both looked at Mrs. Ditchwald. She wore the long cotton dress of a math person, and flat shoes.

We both looked at Mrs. Ditchwald. She wore the long cotton dress of a math person, and flat shoes.“She’s a pawn of the system,” I said. “And look at those ridiculously flat shoes; she could heat up the bottoms of those things and iron shirts with them. She’s an institutional schlep. All she cares about is her crazy math problems and not appearing sexy. Do you think she has a boyfriend? Do you think Janitor Fife ever gives her the look-see?”

“She’s married, for God's sake.”

“Such petty minds as hers I will never understand. Will you? Do you care how many apples Bill has left if his father gives him sixteen but then takes away three?”

“Actually, Martin, yes, I do. It is imperative that I know. I’m trying to get straight A’s in this class.”

I thought of rolling my eyes again, but decided at the last minute to control them. I could not afford to offend Kelly. I took another long drag from my cigarette and looked up at the brown underbelly of a light fixture, where I blew a large cumulonimbus of smoke. “What could a person such as Mrs. Ditchwald have to do with something as stupendous as The Great Hole?”

Kelly looked up to see what I was looking at. I suppose she thought it was a spider. Actually, there was a spider now, a small brown one, descending on a strand of web; I mentally named it Vaughn Spindlenuts. “Oh, I don’t know,” said Kelly. “Maybe she’d be mad about it because it’s her math class and you’re dissing it.”

Oh, how Kelly McGowan could work the italics function! I flicked another ash, harder this time, sixty-nine feet out the open window and into a thirty-gallon vat of holy water, where it hissed, vaporized and died. I looked down to pet my hole. I slowly stroked it. “Kelly. Your tone has changed. You know it has. Do you know how much that hurts me?”

Oh, how Kelly McGowan could work the italics function! I flicked another ash, harder this time, sixty-nine feet out the open window and into a thirty-gallon vat of holy water, where it hissed, vaporized and died. I looked down to pet my hole. I slowly stroked it. “Kelly. Your tone has changed. You know it has. Do you know how much that hurts me?”“Martin, please…”

I needed a fat lie just then, and it came to me. “Ms. McGowan. I don’t need you, you know. I can do this by myself. I’m offering you a job, and a good one. If you don’t see this as history, then think of it as regular employment. Think of it as another entry on your resumé, if that’s what it takes for you. This is a job, and I need a secretary. Case closed.”

I had hurt her feelings. I instantly regretted my words, instantly wished I could take them back. I would get on my knees and beg Kelly if I had to.

Just then, something snored. As I located the source, inspiration struck. I gestured to our right, where Brian Malinowski made the obscene noises of an unconscious dork. A string of drool hung from his bottom lip, seeped over the round edge of his desk, and reached to the floor where it formed a lake that reflected his fat face. “Look at Brian there,” I said. “Do you think he knows how many apples Bill has left?”

Just then, something snored. As I located the source, inspiration struck. I gestured to our right, where Brian Malinowski made the obscene noises of an unconscious dork. A string of drool hung from his bottom lip, seeped over the round edge of his desk, and reached to the floor where it formed a lake that reflected his fat face. “Look at Brian there,” I said. “Do you think he knows how many apples Bill has left?”“No way,” said Kelly, returning to her old self. “In fact, he told me yesterday that he thought Bill had bananas. Can you believe that?” Kelly shook her head and sighed. “He’s a fricking moron.”

I dropped my cigarette to the floor and fatally injured it with the toe of my loafer.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” I said. “And I think he might be addicted to pornography. He was with me at the beginning, but now look at him. He couldn’t stay the course. He forsook me, just like the disciples forsook Jesus. In fact, look around you, Kelly. They have all forsaken me. No one understands—not one! Only you know what I’m about.” I stared hard at Kelly’s awesome blue eyelids. “You alone are left.”

Kelly came aboard that minute, and did things ever change in my drilling speed. In four weeks, the hole was finished, just as Kelly said it would be. To this day I do not believe that I could have finished The Great Hole a week ahead of schedule were it not for the support of a woman, for the belief of a woman, for the inspiration of a woman.

Brian missed us passing through the last centimeter of desk, as did every other moron in my class. Only Kelly was there. She cried, as did I. It was a moment to remember. We held the pencil together and drilled, Kelly and I, palms pressing palms as that final eight-sixteenths of a centimeter disappeared beneath the lead of our pencil/drill.

Mrs. Ditchwald pulled me harshly from the room the next afternoon, pulled me by the tender apex of my right ear into the hall, and down to the office of Sister Dominna. It is possible that a boy jealous of my relationship with Kelly tipped off Ditchwald—but who cares how she found the hole? Sometimes a person cannot feel pain. And sometimes, if the high is high enough, a person can even smile through it.

“So many students sit in that desk throughout the day!” spat Dominna, cracking her pointy black knuckles. “And yet Ditchwald tags you.” She narrowed her eyes. “I have insight into you and that little hole of yours, Zender. May I salvo a query into the hows of your arrest?”

“I think that you already know, Herr Dominna. So say it. Say it with all your might for the benefit of all my readers through the eons of time. Say it with gusto before the commencement of my sacred punishment.”

“I think that you already know, Herr Dominna. So say it. Say it with all your might for the benefit of all my readers through the eons of time. Say it with gusto before the commencement of my sacred punishment.”“Gladly, Master Martin: You signed the damn thing!”

Sometimes, if the high is high enough, a person can smile through any sort of temporal discomfort.

© 2006 by Martin Zender

No comments:

Post a Comment